Dos Mosquises and the Sea Turtles

This blog post reproduces the main content of the previous post in English. We want to fulfil the promise we made to the president of Fundamar Miranda, Eduardo Meléndez. Another translation into Spanish follows. The original German version can be found at the following link → https://www.sy-magodelsur.de/2025/08/27/dos-mosquises-und-die-schildkroeten/.

Fundamar Miranda

The origins of scientific work date back to 1956, when the La Salle Natural Science Society began archaeological investigations on Los Roques. In 1967, the Venezuelan government approved the construction of facilities by a private foundation to support researchers and protect the environment on the Mosquises. Today, the turtle station is backed by the Francisco de Miranda Private Foundation for Marine Research (Fundamar Miranda for short), which was founded in 2013 and to which the government transferred ownership of the existing facilities in 2014. The turtle station began its work four years ago. Two years ago, the buildings were partially renovated. The station is run by two teams of five men each, who take turns every month. One month of service in isolation, one month off with family and friends. Interestingly, all the employees come from remote areas of Venezuela, some even from the mountains. We are told that they are more committed to such matters than coastal dwellers. The team we met consists of Edgar, José, Leonardo, Leonel the marinero and Thomas. Coincidentally, the day after our arrival, the boss, or to be more precise, the president of the foundation, Eduardo ‘Edward’ Meléndez, arrived and stayed for a few days. We had interesting and informative conversations with everyone and felt very warmly welcomed.

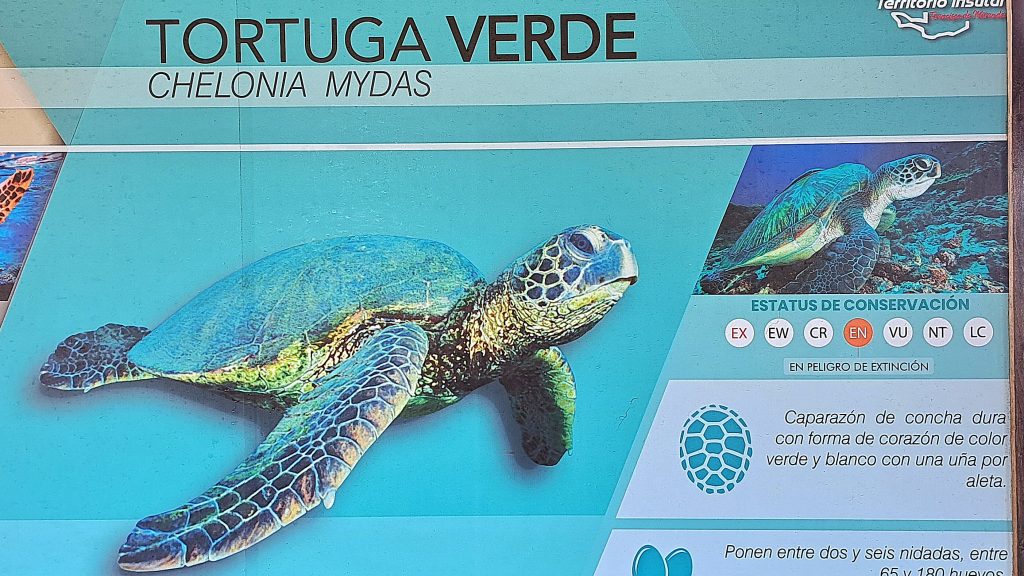

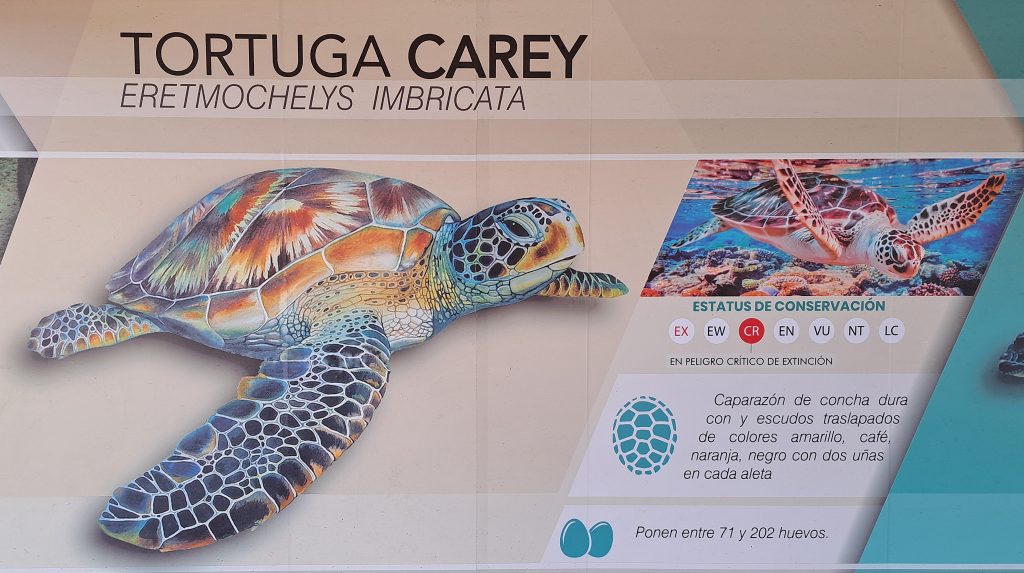

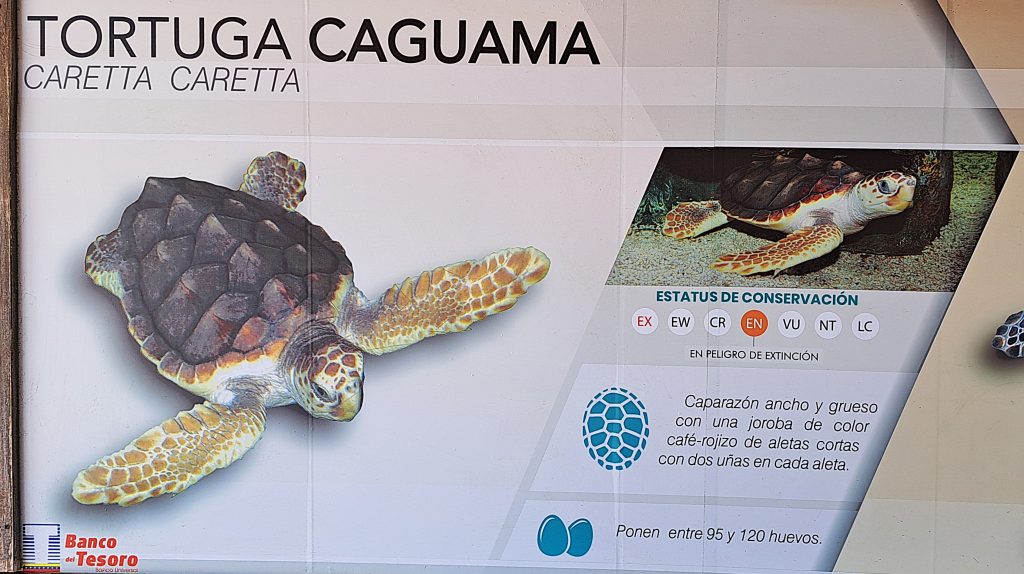

The station’s mission is the long-term conservation of local turtle populations. Four species are found on or near Los Roques.

- The Green Sea Turtle / Tortuga Verde (Chelonia mydas)

- The Loggerhead Sea Turtle / Tortuga Caguama (Caretta caretta)

- The Hawksbill Sea Turtle / Tortuga Carey (Eretmochelys imbricata)

- The Leatherback Turtle / Tortuga Laúd (Dermochelys coreacea)

The station is dedicated to the first three species. In the case of Leatherback Sea Turtles, it is practically impossible to keep hatchlings and juveniles in captivity due to the species‘ special ‘diet’. They feed mainly on jellyfish, and the people here cannot provide the quantities of jellyfish required for the turtles‘ diet. It’s really strange what ideas evolution comes up with. Of all species, the largest sea turtle feeds on slimy creatures that consist almost entirely of water. It seems like a miracle to us that Leatherback Turtles are able to meet their nutritional needs at all – after all, an adult leatherback turtle eats between 10 and 100 kg of jellyfish per day.

Works at the station

Work at the station mainly consists of caring for the animals in captivity. The water in the tanks is changed every second day, and fish are caught six days a week to feed the animals. Once a week is a fasting day. Of course, the station’s technology also has to be maintained and serviced: the seawater pump for changing the water, the station’s power supply, the open shuttle boat that connects the station to the outside world including picking up food and 400 litres of fresh water from Gran Roque about once a week – as a European, you have to think about that: 400 litres of water for one week and 5 people – and so on and so on. In between, short-term tourists are looked after, or strange ‘permanent guests’ like us. The highlights of the job are definitely the days when new eggs are collected for the next generation of hatchlings. To do this, egg-laid sites are sought out on the surrounding islands and carefully excavated. The eggs are laid at a depth of up to 1.5 metres. That means there’s quite a bit of digging to do. Depending on the species, there can be up to 200 eggs in a single (!) clutch, although it should be noted that the animals lay up to three clutches between June and October, which means that far more eggs increase the chances of survival for the species.

After hatching, the hatchlings, which are only a few centimetres in size, are transferred to saltwater tanks. There they are protected from their enemies. These babies and young animals are fed six days a week, with one day of fasting. They are mainly fed small fish, freshly caught each time by one of the employees. The water is changed every other day. The day of our visit is actually a fasting day, but since the Estacioneros have realised that we are, in a sense, experts, the animals are lucky and get a little extra food.

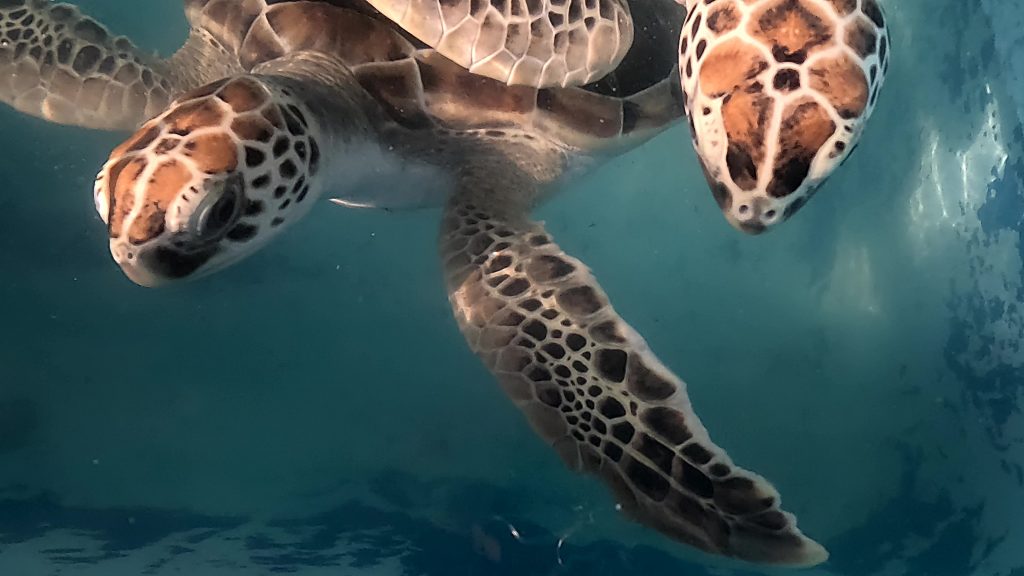

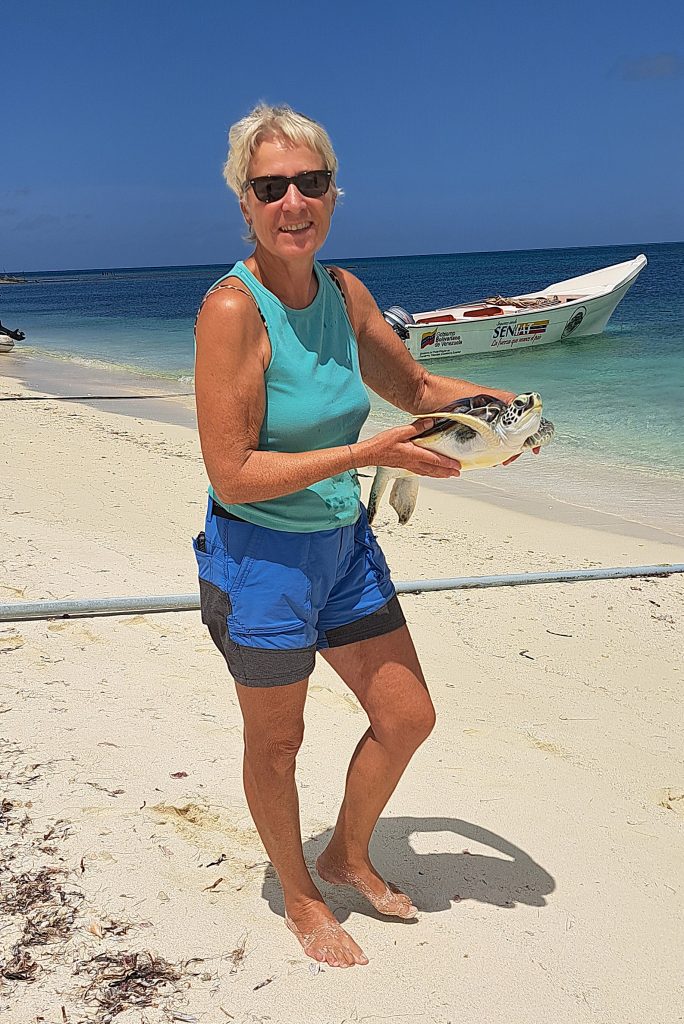

Every day at this time of year, one or two protégés are released. It is always turned into a small event for visitors to the station, especially when there are children among them. Which is almost always the case. Anke is even asked by the presidente himself if she would like to release a turtle. Edgar has skilfully orchestrated the process.

The exciting thing about the release is the moment when the animals come into contact with seawater for the first time on the beach. This seems to be the moment that gives them the basis for orientation, the moment when they ‘calibrate’ their inner compass. This experience is essential for these animals to return to the beach where they have been hatched after about twenty years and lay their own eggs there.

Anke is carrying a small Green Sea Turtle to the beach. After a short speech in which she wishes the turtle a beautiful and long life, many eggs and hatchlings so that the species can thrive – we are dealing with a female animal – she names this turtle Esperanza (hope).

A few comments on the necessity of the turtle station’s work. In nature, under the usual living conditions of the species presented here, only 1 to 2 animals per 100 eggs survive; our dialogue partners on the island even speak of only 2 to 3 per 1,000. The eggs are eaten by crabs, lizards and birds. Furthermore, they are not as hard-shelled as bird eggs, so they are naturally more fragile. Another problem is seawater. The salty water destroys the shells. The eggs must therefore be laid in a place that is safe from the influence of seawater, which the turtles do not always manage to do. After all, a female lays up to three clutches within several weeks.

The next major natural loss occurs after the animals hatch. The hatchlings are only a few centimetres long and weigh only a few grams. Once they have dug their way out of their underground nest, birds, crabs and, of course, fish prey on them as soon as they reach the water. Occasionally, they are even eaten by their own species. Today, climate change is adding further problems.

- Rising sea levels are causing some of the breeding beaches to become narrower.

- Higher sea levels mean that deeply buried clutches are increasingly exposed to salt water.

- Higher temperatures mean that in certain places only female animals hatch, causing a dramatic shift in the sex ratio. The reason for this is that the sex of sea turtles is not determined by chromosomes, but by the nest temperature during embryonic development. There is evidence that a balanced sex ratio is achieved at 29.5°C. We have not verified whether this applies equally to all species and at the same threshold temperature.

With this in mind, it is easy to understand why the two Dos Mosquises teams are so proud of their work. In 2024, they managed to release an impressive 1,732 animals.

Also at the end of the day: Martin is already at the dinghy and is about to prepare it for the short hop on board.

We hope that Esperanza will fulfil the hopes and expectations placed in her and we wish her all the best for the rest of her life. Finally, paddling around in the water, she seemed to be in good spirits and appeared to be enjoying her new freedom of movement in the seemingly endless ocean.

With this in mind, stay positive!

Martin and Anke